It’s a story I’ve shared in our book, Practical Wisdoms @ Work: someone who held authority in my life told me that, while it was okay that I was on antidepressants at the time, I shouldn’t be on them for more than a year. Here’s another story: while discussing my depression and mental health, a family member told my sister that I should just “do something I enjoy” to cure myself. Both of these people cared about me and wanted me to be happy again. They just didn’t get it.

If you’ve dealt with mental illness, there’s a good chance you can think of a few stories in your life that are similar to mine. People you know well, and some not-so-well, seek to impart wisdom on how you can choose a healthy brain. They mean well, but they often make you feel worse. My mental health struggle is primarily with depression. The examples come from my experience, so they will focus on responses to depression. However, you will likely recognize some of these pieces of unhelpful advice even if you have a different mental illness.

“Just Do Something You Enjoy”

If a person is sad, they should do something that makes them un-sad. Watch a favorite movie, go dancing, take a walk in nature – do something that you enjoy to lessen the sadness. Depression is popularly conceptualized as just being Very Sad, so it makes logical sense for people to apply remedies for sadness to depression. Unfortunately, the popular understanding of depression isn’t accurate. My depression typically manifests instead as a lack of energy, dearth of motivation, and disinterest in even my favorite things. Yes, that means I can’t really enjoy anything.

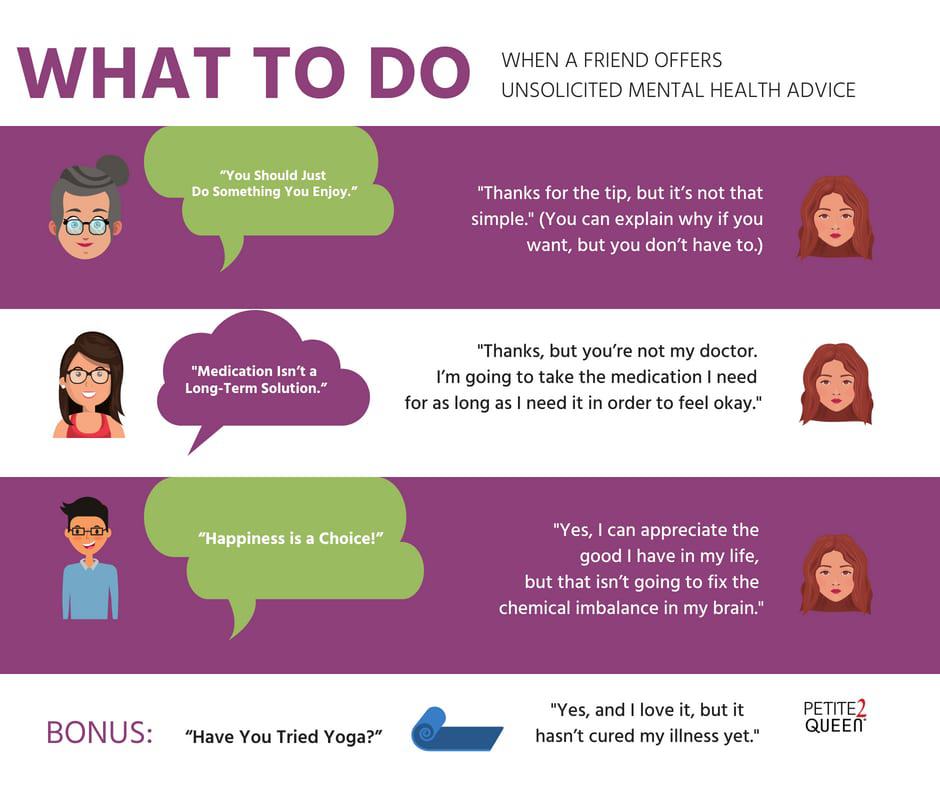

When people suggest that you “just do something you enjoy,” it means that they don’t understand mental health or your mental illness. Enjoyment might not be possible for you, even in your favorite activities. Perhaps your mental illness makes you go overboard on the fun. Whatever the case, you have a choice here to explain to your loved one how your mental illness operates. Of course, explaining such a complex and sensitive topic is exhausting, especially when you have to do it repeatedly. If you don’t have the energy to educate them, you might suggest that your friend simply Googles it herself.

The tip to just do things you like also glosses over the fact that of course you’ve tried that. When your mental illness gets bad, doing things you enjoy is probably the first thing you try to get back on track. It’s realizing that your favorite activities no longer help that is actually one of the most frustrating and scary things about mental illness. If you’re like me, you don’t necessarily like being reminded of that. Ask your friend to not tell you to “just do something you enjoy” again.

“Medication Isn’t a Long-Term Solution”

I’ve only been told this once in person, but the message is everywhere across traditional and social media. Medication isn’t a long-term solution. Medication changes your brain. You shouldn’t become dependent on medication to feel okay. I’m sorry, but my brain doesn’t tend to meet deadlines on when it should start producing enough serotonin. Of course the medication alters my brain – that’s the whole point! It makes my brain produce enough serotonin for me to experience a normal mood. And I’m going to take the medication I need for as long as I need it to not be debilitatingly depressed.

Of all the unhelpful advice I’ve received, this one bothers me the most. The people who give it are almost never doctors, much less psychiatrists or psychologists. These people tend not to appreciate that a sick brain is just as bad as any other chronic illness. Most of them would never suggest that a person stop taking their blood pressure medication to avoid becoming “dependent” on it.

Remind someone who tells you to stop taking medication that they are not a doctor. You can assure them that you are working with actual doctors, who understand how your medication and illness work. Tell them that your medication helps and that you’re hurt that they would want to push you back into suffering. It’s destructive advice, and it should not be repeated.

“Happiness is a Choice”

The idea that happiness is a choice comes from encouraging people to look on the bright side and appreciate what they have. Both of those things are usually good. Neither of those things apply to mental illness. Yes, I can appreciate the love I have in my life, but that isn’t going to fix the serotonin deficiency in my brain.

The idea that mentally ill people need to just take better care of themselves is pervasive in our culture. Sure, yoga, meditation, exercise, and healthy diet can help a mentally ill person feel better. However, with my depression, I am not always able to do those things. I cannot always “choose happiness” because sometimes I can’t even summon the energy to change out of my pajamas.

Regardless, things like yoga and a healthy diet cannot be expected to cure an illness – only help manage some symptoms. I don’t want to dismiss people who have managed to lift their mental illness (usually depression) with these things. But I also want to remind people that these things won’t work for everyone. Mentally ill people should work with their doctors to find the best treatment plan for them. “Choosing happiness” usually isn’t one.

Friends Can Still Help

None of this is to say that friends and family can’t ever offer advice on mental health. If your sister found an article about a breathing exercise that can help with panic attacks or your favorite blog lists ways to work with depression, those things can be very helpful. The key is that it isn’t judgmental or self-righteous. Your loved ones should do the research necessary to understand your illness and give you love and support accordingly. You can tell them so.

Petite2Queen provides virtual mentoring to young women in life, at work, and in sales. Follow us for more practical advice you can put to use to improve your life and career.

Rachel Whitbeck is the Director of Communications & DEI Advisor at Petite2Queen. She has a PhD in Sociology from the University of Limerick in Ireland. Rachel uses her experience in writing, editing, and research to develop content that appeals to and is reflective of the diverse millennial woman.